Ololokwe: a horseshoe-shaped cliff a mile long, up to 1500 feet high, and covered in a patchwork of overhangs, slabs, and vegetation. Despite its length, this gneiss monolith does not fracture continuously and has yielded relatively few routes and even fewer moderate ones.

With 4 days and limitless optimism, Fish, Nick Quintong, and I departed from Nairobi with the goal of avoiding a vision quest while exploring a new line. This would be my last climbing trip in Kenya, and we focused our attention on the far West face of the mountain, where the height and angle is at a more human scale. Fish spoke of an area dubbed The Tulip, and photos revealed several appetizing aretes that could be moderate enough for us. After an eventful drive, we arrived in the surprisingly green and always stunning landscape north of Isiolo.

Our recce led us up the Wamba road, where we turned North from Larata and drove into the bush to approach the base of the mountain. Luckily Nick didn’t mind some trophy scratches on his paintjob, and we bulldozed our way through dense thickets and dry laggas until we found a manyatta where we could park the car. Anything to avoid walking.

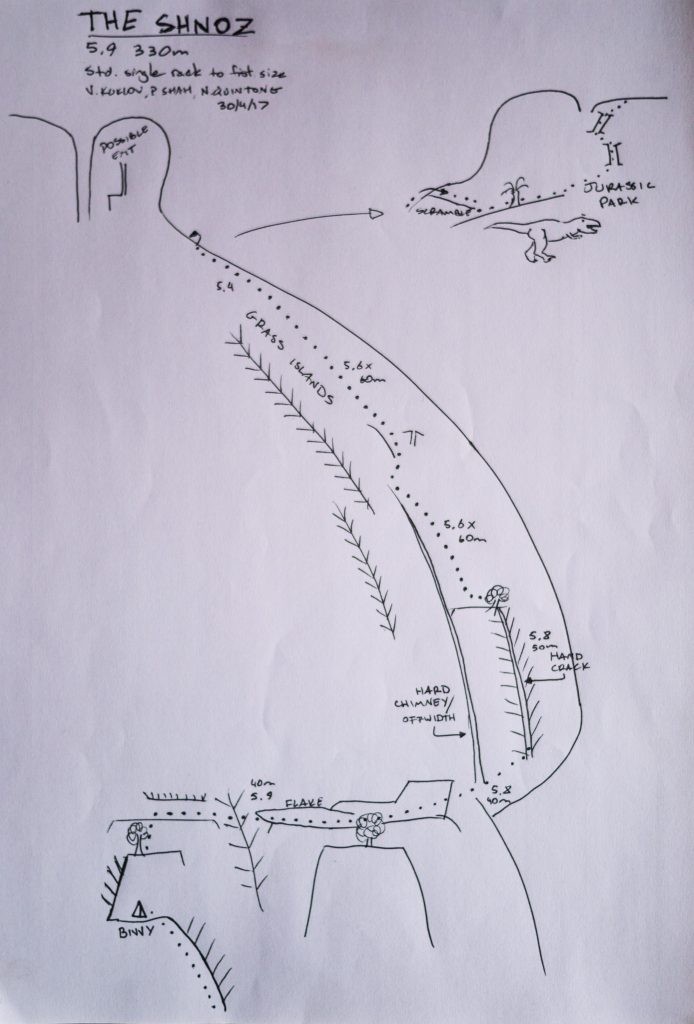

We scoped the wall as best we could, and decided that the rightmost blunt arete looked the most suitable: low angle, exposed, and with visible features and cracks. Lower on the feature, we could even spy a long, thin crack that was invisible from the road. It wasn’t the Nose, but it certainly was a Shnoz.

Given the height of the cliff and the length of the approach and descent, we knew we had to bivy at some point. With no obvious ledges on the route, and reluctant to carry the water required for 2 days, we decided to bivy at the base and try to complete the route in a day to get back to Sabache camp by evening. We packed hammocks, a bit of food and water, and planned to find a suitable place close to the start. The weather looked stable so we left the tarp and took one raincoat. Our intrepid guides, Jackson and Anthony, showed us the way up the hill on elephant tracks, which made for surprisingly easy walking up to the last few scrambles.

Loading up at the manyatta before heading into the bush

Once we were closer to the base, we scrambled up a few slabs and found a perfect ledge. Covered in soft vegetation and surprisingly devoid of animal shit, we quickly set up hammocks and couldn’t believe our luck in finding such a 5-star bivy spot. The views stretched out to Mt Kenya, and with plenty of daylight we settled in for a relaxing evening.

Pretty quickly, we noticed dark clouds gathering in the South. A wind began to blow, whipping the dust in the plains below into a massive cloud. A sheet of water appeared to our left, erasing the hills that had been there a few minutes previously. In a moment of inspiration, Nick proceeded to strip down, hide his clothes and climbing gear in a waterproof bag, and sat down to wait. With some confidence, I predicted that due to the wind direction and atmospheric conditions, the rain would surely pass us by.

The first drops were fat and quickly grew in number as the rain clouds flanked us and crashed over the top of the wall. Pretty quickly, the three of us were down to underwear and clustered around the fire, where Anthony and Jackson were also resigned to the soaking, though reluctant to get completely weird with us.

After drying out and getting dressed, we ate and got into our hammocks and spent a long night pretending to sleep. The wind blew away any warmth from the fire as we each silently swore never again to sleep in hammocks without insulation. The welcome sunrise saw Anthony and Jackson heading down as we headed up.

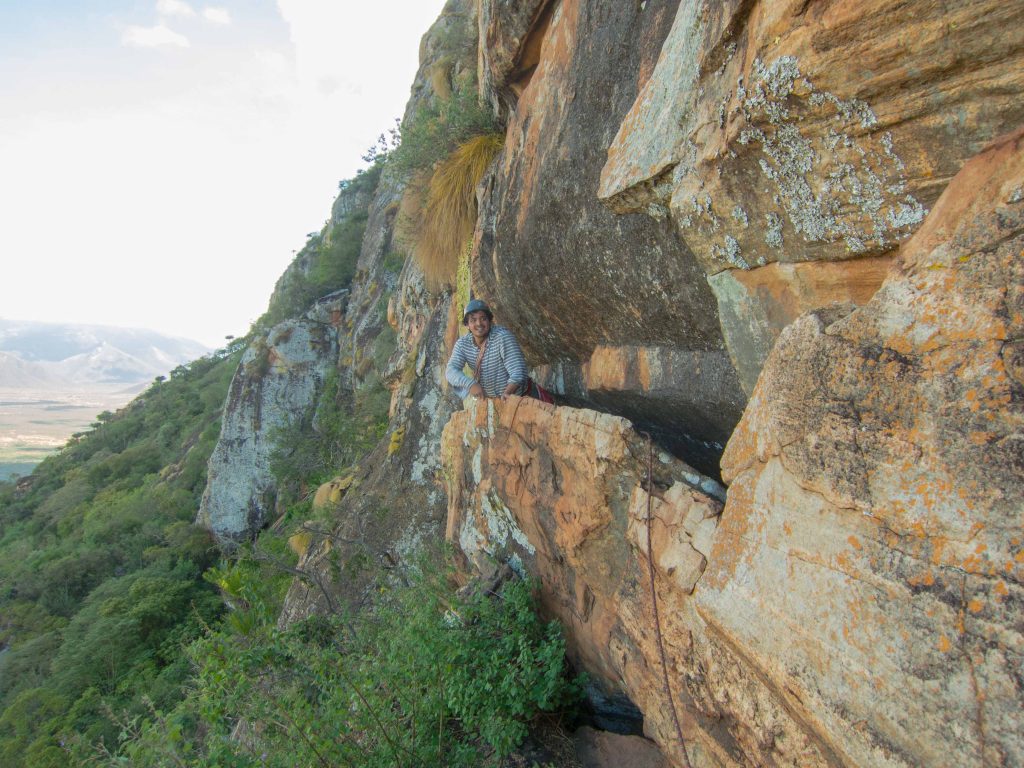

The first pitch traverse

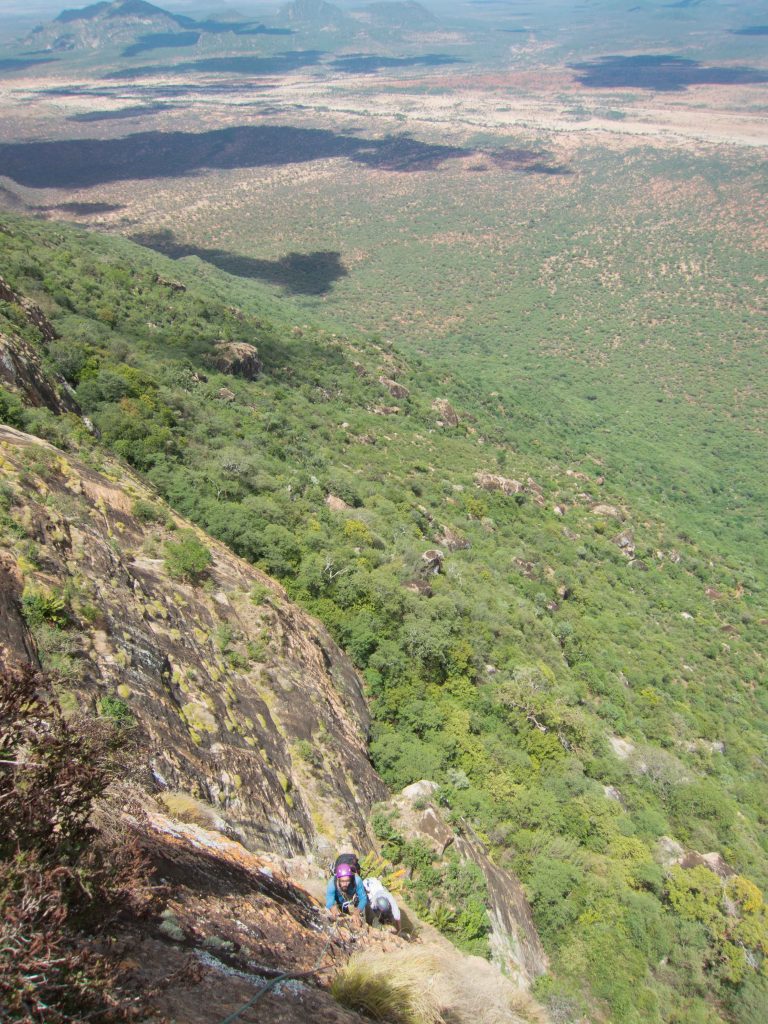

A team effort of dynamic traversing and backpack wrestling saw us lead the first pitch across a ledge system that would carry us to the cracks and arete we had seen the day before. Fish led the next pitch up to the base of the beautiful “thin crack”. This turned out to be a monster squeeze/offwidth – 40m long and apparently unprotectable. Staying realistic about my abilities, I found another corner crack farther right that took pro and gave back moderate, fun climbing up on to the Shnoz itself. Another 20m of plate pulling and crimp crushing without any real protection led me to a belay. Our position on the arete yielded panoramic views in all directions, with hardly a dark cloud in sight. Surely it wouldn’t rain again. Nick took over, pushing the rope a full 60m up some beautiful face climbing before finding a creative belay.

Fish finding our way up to the crack

A quick transfer and Fish is off

Fish then brought us 60m higher, where the angle eased off considerably and we could unrope and scramble up to the bridge of the Shnoz to find an exit. We explored a direct exit up the final headwall before deciding the safer option was to traverse right off the arete and find a way out of the neighboring gully. The first drops started to fall as we moved into the vegetated gully, dubbed Jurassic Park.

Once inside, the rain began to fall steadily, and wouldn’t stop until the next morning. We rushed to find an exit before the rock was too soaked to climb, or we had to bivy in a gully that likely would become a torrent in heavy rain. I hastily led up a series of squeeze chimneys, through loose vegetation, and over packed kitty litter, desperate to reach the top in one pitch. What followed was one of the worst pitches I’ve had the pleasure of climbing in Kenya – it was fitting that Ololokwe wouldn’t let us through with just the easy climbing below. I laughed as I thrutched up to the final bush belay, somehow glad that my last pitch of climbing in Kenya turned out to be a complete horror show. Nevertheless, we were all ecstatic to have reached the top and in good style!

It was now around 4 pm and the clouds were only getting heavier. We knew the descent was the crux of the whole adventure, so we threw on our packs and headed out on a circumnavigation of the rim along elephant trails, hoping to arrive at familiar ground on the far side of the plateau.

After two hours of walking in the pouring rain, we were soaked and in high spirits. We knew that another group from MCK was planning to hike and camp at the top of the mountain, but given the rain we were doubtful that we could find them. Darkness was approaching, and none of us knew the right way down, so we were anxious to find the right trail before we would have to stumble through the bush by headlamp. On a whim, we sent a few shouts and whoops out into the bush and to our immense surprise we got a few back. Relief flooded through us as we quickly met a few guides and walked to the top camp.

Unfortunately, we quickly learned the situation: most of the group had already gone down because their pack donkeys had gotten lost on the way up. Everyone was very low on water and food, and there were no guides available to help us walk down the mountain in the dark. We were in for another night in the open, with a few bars and a liter of water between the three of us. Nick and Fish immediately set about building a shelter while I went through the seven stages of grief. The rain kept falling, but pretty soon we had a cozy lean-to in a dry spot under a tree. After drying ourselves by the fire, we settled in for the night, laying shoulder to shoulder under the lean to with our feet poking out into the rain.

Unfortunately at about 1am the real rain started and pretty quickly any vestige of shelter disappeared. We tried to squeeze ourselves into the far corner of the lean-to, away from the open side, but this proved futile as the wind and torrential rain drove in through every gap. After an hour or two of bearing the confinement and cramps, we decided to surrender the idea of the rain subsiding and us getting any sleep, so we dove out and crowded around the remaining fire. What followed was a long night of spinning in circles, alternating which side got wet and which side got dry . Our morale remained high as we tried to appreciate the situation we had found ourselves in.

By first light, however, we were all eager to get out of there. The rain subsided and brought an incredible inversion to the plains below. We threw on our soaked packs and stumbled down the hill to camp.

One last mission remained, however. Nick’s car was still at the manyatta and the rain meant that the laggas would now be flowing. Apprehensively, we walked in and found that the crossings were actually milder than expected. Nick zipped back to his car and drove it out through the bush and mud like a hero, putting us back on the road and on our way to Nairobi. With no sleep for 48 hours, and hardly anything to eat, we took turns driving until we were finally each in our beds. We still can’t quite believe that we were able to climb a new route on such an imposing and incredible cliff!